It then presents evidence regarding the adverse effects on workers who work such irregular and on-call work schedules, in contrast to those with more regular shift times. It will also present evidence of the beneficial effects on work-family integration and work stress when employees report having input into the scheduling of their work and/or flexible work schedules. In Congress, the Schedules that Work Act of 2014 (H.R. 5159), would extend this still further in scope. This new right would target four key industries where irregular scheduling has been concentrated.

It would require a minimum of 14 days advance notice for posting schedules. It also would mandate a minimum reporting payment for call-off and one hour's pay for split-shifting practices. Specifically, the bill would require employers to inform workers in writing of their expected minimum hours and job schedule, on or before their first day of work.

If the schedule and minimum hours happen to change, the employer would be required to notify the employee at least two weeks before the new schedule comes into effect. Employers would begin to have to compensate workers when they are sent home from work earlier than planned, paid at their regular rate for four hours or the total length of the workers' shift if the shift is less than four hours. Full-time employment often comes with benefits that are not typically offered to part-time, temporary, or flexible workers, such as annual leave, sick leave, and health insurance. However, legislation exists to stop employers from discriminating against part-time workers so this should not be a factor when making decisions on career advancement.

They generally pay more than part-time jobs per hour, and this is similarly discriminatory if the pay decision is based on part-time status as a primary factor. The Fair Labor Standards Act does not define full-time employment or part-time employment. The definition by the employer can vary and is generally published in a company's Employee Handbook.

Companies commonly require from 32 to 40 hours per week to be defined as full-time and therefore eligible for benefits. In 2014, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors approved new protections for the city's retail workers, which took effect on January 5, 2015. The measures are intended to give hourly retail staffers more predictable schedules and priority access to extra hours of work available. The legislation applies to retail chains with 20 or more locations nationally or worldwide and that have at least 20 employees in San Francisco under one management system (thus affecting about 5 percent of the city's workforce).

The ordinances require businesses to post workers' schedules at least two weeks in advance. Workers will receive compensation for last-minute schedule changes, "on-call" hours, and instances in which they are sent home before completing their assigned shifts. More specifically, workers will receive one hour of pay at their regular rate of pay for schedule changes made with less than a week's notice and two to four hours of pay for schedule changes made with less than 24 hours' notice. Finally, it prohibits formula retail employers from discriminating against employees with respect to their rate of pay, access to employer-provided paid and unpaid time off, or access to promotion opportunities. This will more forcefully protect employees on part-time status, for example, by providing part-timers and full-timers equal access to scheduling and time-off requests.

However, the right to extra hours is often not fully respected at workplaces. The reason given for this is that in service sectors labour needs vary depending on the time of day and the day of the week, and so more part-time workers have to be hired. Random extra hours offered at short notice can be difficult for employees to accept because they have planned their own and possibly their families' lives based on the known work schedule. For the right to extra hours to benefit all concerned, employers should do more to plan work shifts.

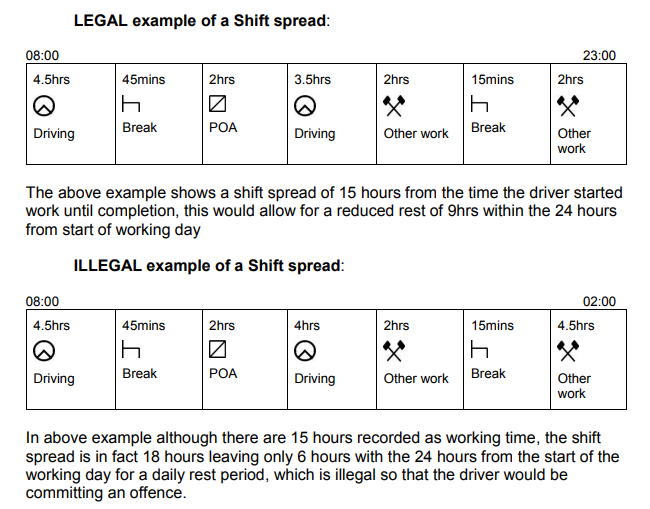

The working time averaging schedules in collective agreements provide scope to place work shifts at times when demand is greatest with due regard for employees' right to extra hours. Sixth, to protect against overwork, employers must secure employees' consent to work with less than 11 hours rest between work shifts and employees must be compensated at a time-and-a-half pay rate if the employee agrees to work such hours. This right is targeted to those who arguably need or value it the most—it must be granted unequivocally if the request is due to a serious health condition, caregiving obligations, educational pursuits, or requirements of a second job. Ninth, employers must offer hours to existing (not just part-time) employees before hiring new staff or temporary workers.

Finally, protection against retaliation is stronger, placing the burden on employers to show that an adverse action against an employee who exercised his or her rights or assisted others to assert their rights, was not retaliatory in nature. Enforcement would include an individual right to pursue civil penalties, in addition to actions by an office of labor standards. One key source of underemployment is that at least periodically, employees are scheduled for fewer hours than they prefer to be working, in days or weeks that are not necessarily regular or predictable.

Thus, the consequent experience of involuntary part-time employment not only constrains the incomes of those workers, but often makes the daily work lives of those individuals unpredictable and more stressful. Interestingly, there is also a nontrivial proportion of workers who actually would prefer to work fewer hours even if it means proportionally less income. Some employers have undertaken fair scheduling initiatives on their own.

Some companies have instructed their local store managers to consider requests for making schedules more stable or consistent week to week, such as Starbucks and Ikea, which provides up to three weeks' advance notice of upcoming schedules. Such workers are also empowered to engage in the key practice of shift-swapping. President Obama has directed the federal Office of Personal Management to initiate more flexible work and workplace options for the approximately 2 million federal employees. The agencies must facilitate conversations about work schedule flexibilities, including telework, part-time employment, or job sharing arrangements.

Supervisors have to confer directly with the requesting employee as appropriate to understand fully the nature and need for the requested flexibility, and carefully respond within 20 business days of the initial request. In addition, other sections provide part-time and job sharing, telework, break times, and private spaces for nursing mothers. Advance notice of schedules is distributed quite differently among occupational groups. Among service workers, production workers, and skilled trades, most employees know their schedule only one week or less in advance. Service and production supervisors, however, are among both those with the shortest and the longest advance notice categories. In contrast, the majority of professionals, business staff, and providers of social services know their work schedule four or more weeks in advance.

Furthermore, approximately 74 percent of employees in both hourly and nonhourly jobs experience at least some fluctuation in weekly hours over the course of a month. Among workers with children, 40 percent report one week or less advance notice and 50 percent say they have no input into their schedule. Employers determine the work schedules of about half of young adults without employee input, which results in part-time schedules that fluctuate between 17 and 28 hours per week. For the majority of employees who work fewer than 40, as well as those with more than 44 hours in a normal week, hour fluctuation is the norm. So, among workers with the longest hours, the 40-hour workweek seems not to be the norm but rather, just a lower bound.

The mean variation in the length of the workweek is 10 hours among hourly workers as compared with nearly 12 hours among nonhourly workers. Among the 74 percent of hourly workers who report having fluctuations in the last month, hours vary by a whopping 50 percent of their usual work hours, on average. Processes to improve the quality of part-time work include granting part-time workers pro-rata earnings and benefits, and rights to request changes in their working hours. It includes "reversibility"—to be able to move back from part-time to full-time hours after having moved from full-time to part-time.

Not only the duration of working hours, but also work schedule predictability can be addressed through legislation. Fostered a move on the part of the British government (termed, "BIS ") in June 2014 to ban the use of exclusivity clauses in such contracts. As the name suggests, part-time workers have fewer hours than a full-time employee.

Part-time jobs typically require no more than 35 hours per week, and may be as few as 5-10 hours. Unlike full-time employees, part-time employees are not guaranteed the same number of hours or shifts each week. For example, a part-time cashier at a grocery store may only work 15 hours one week, and then 20 hours the following week.

Part-time workers sometimes have the option of picking up additional shifts to cover for coworkers who call in sick, or for working extra hours during a particularly busy time of the year. Workers over the age of 18 can choose to opt out of the 48-hour limit for a certain period or indefinitely. This agreement must be made voluntarily and in writing by the employee; it can also be cancelled by the employee by providing the employer at least seven days' notice.

However, signing the opt-out clause does not prevent workers from refusing to work for more than 48 hours per week. Any hours worked above the 48-hour per week fixed or, where appropriate, average legal working hours must be voluntary. Canada has legislated reporting pay requirements in its federal sector and in several of its provinces. In Ontario, Saskatchewan, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Alberta, compensation is mandated for a minimum of three hours at the minimum wage.

In Quebec, Prince Edward Island, and Manitoba, compensation is mandatory at a minimum of three hours at the employee's regular wage. In the Northwest Territories and Nunavut, employees are owed four hours at the regular wage if they show up to work their shift and less than four hours of work is provided. Finally, employees have the right to refuse overtime without repercussions in Saskatchewan, Québec, and Yukon. A recent poll of 1,000 U.S. adults by the Huffington Post and YouGov poll documents the extent and incidence of underemployment, by considering a broader scope than just working part-time hours or not working at all. It asked, "If you had the opportunity to work one more day per week, and receive 20 percent more pay, would you take that opportunity? Over half the sample, 52 percent, would (see Appendix Table A-1 at the end of this report).13 There were no real gender differences in this regard.

By age, the rate was almost 60 percent in the 18 to 29 age bracket, then progressively lower by age, but still at a high 48 percent among those age 45 to 64 (then rising again among those 65+). By family income level, not surprisingly, the underemployment rate is higher among those reporting less than $40,000 per year . The rate becomes progressively lower up to $100,000, but still remains at 43 percent among those families with incomes over $100,000 per year. By race, a preference for more work hours and proportionately more pay is more prevalent among blacks and Hispanics , though it is still a high 47 percent among whites. Most pertinently, by employment status—it is 60 percent among part-time workers. Nevertheless, the rate is still a high 50 percent among full-time workers.

Interestingly, not unlike the Pew poll, half of those outside the work force—retirees and homemakers, would prefer to work at least one more day per week, and among students, this was 65 percent. The persistence of all these various forms of underemployment is at least partly responsible for the inability to achieve full economic recovery and expansion. Household earnings are constrained not only by stagnant wage rates,14 and the lack of any pay for extra hours of work,15 but by workers not able to find or get additional, preferred hours of work.

Determining when part-time workers or workers with flexible hours are entitled to premium payments requires reference to their contracts, collective agreements and national law, which will state when overtime payment starts. In some countries or situations part-time workers only get overtime premiums once they have worked more than the normal full-time hours for comparable workers. The important thing is to assess national law, the worker's contract, and any collective agreement, to identify the point at which overtime is deemed to start.

Generally, an FTE is a way to express a part-time workforce in terms of full-time employment. This calculation is sometimes done by taking the number of total hours worked by all part-time employees and dividing by the number of hours that are considered to be a full-time schedule. For example, if an employer has 10 employees who work 20 hours per week and considers 40 hours a full-time schedule, this would equate to 5 FTEs. Keep in my mind that some laws, including the ACA, require employers to use specific calculations to determine the number of FTEs. The ACA requires that employers add all the hours worked by part-time employees in a month and divide by 120. The most common benefits include health insurance, as well as dental, vision, and life insurance.

Employers that offer insurance will usually pay for some (or even all!) of the monthly cost of the policy. Most full-time employees will also be eligible for paid time off through federal holidays, vacation days, and sick days. Some employers offer their full-time employee's retirement options such as a 401 plan , as well as other company-specific perks such as reimbursements for childcare, a fitness membership, an education stipend and stock options. For purposes of determining employer shared responsibility payments, the IRS identifies full-time employees as those who work an average of 30 or more hours per week .

Full-time employees may get paid by the hour just like part-time employees, or they may receive a flat salary. This is not usually something that can be negotiated with an employer. Exempt employees, on the other hand, always earn the same salary no matter how many extra hours they work.

First, the Minnesota bill would apply to all employees , not just in the retail sector. Second, the amount of advance notice would be three weeks, not just two, for employers to post employees' initial schedules, including on-call shifts, and employees must be notified of schedule changes at least 24 hours prior to the change. Third, employers must get consent from workers in order to add hours or shifts after the initial schedule is posted. Fifth, employees would be entitled to receive reporting pay of four hours or the duration of the shift, whichever is less, when their employer cancels or shortens a shift with less than 24 hours' notice.

Given the evidence presented here and in other, recent studies of the relationship between long, irregular or unpredictable work hours and work-family conflict, which policies might prove effective at mitigating the conflict? Other countries have taken steps to limit the unpredictability of work schedules and promote a legally protected ability of workers to adjust their work schedules? 48 Regarding the latter, an important first step has been proposed in the U.S. The evidence presented suggests that providing that "right" at least on an individual, case-by-case basis would be helpful in part because access to more flexible working arrangements is so disparate by sector. A sampling of retail sector workers in and around New York City finds that only 40 percent of such employees have a minimum number of hours set per week . Moreover, a quarter of them work "on-call" shifts, with most not finding out if they are needed at work until two hours before the start of the shift.

The definition of full-time hours is a classification set by law to determine a reasonable standard for working hours and to specify the maximum hours that hourly workers can work in a single week before being eligible for overtime compensation. The number of full-time employees help Many employers also reserve certain benefits for employees who work full-time hours. According to the Fair Labor Standards Act , employees who work more than 40 hours per week and aren't salaried must be paid time-and-a-half for every hour worked over 40 hours.

Some employers consider employees that work at least 35 hours per week to be full-time workers and offer overtime pay for every hour worked past 35. However, salaried workers aren't always entitled to more money for working more than 40 hours-per-week. In Connecticut, a non-exempt employee in the mercantile trade and restaurant industries who reports for duty must be paid a minimum of four hours of pay at her regular rate . Non-exempt employees in the District of Columbia must be paid for at least four hours, payment at the employee's regular rate for the hours worked, plus payment at minimum wage for the hours not worked. In Massachusetts, non-exempt employees , who are both scheduled to work at least three hours and report on time must be paid for at least three hours at no less than the minimum wage even if no work is available.

In New Hampshire, non-exempt employees , must be paid not less than two hours' pay at the regular rate of pay if an employee reports to work at the employer's request . The labor market continues to recover, but a stubbornly high rate of underemployment persists as more than five million Americans are working part-time for economic reasons (U.S. BLS 2015a; 2015b). Not only are many of this type of underemployed worker, by definition, scheduled for fewer hours, days, or weeks than they prefer to be working, the daily timing of their work schedules can often be irregular or unpredictable. This both constrains consumer spending and complicates the daily work lives of such workers, particularly those navigating through nonwork responsibilities such as caregiving. This variability of work hours contributes to income instability and thus, adversely affects not only household consumption but general macroeconomic performance.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.